Poem ‘Timeless in Tir Na Nog’ by Alan Wherry

In the eternal presence of Tir Na Nog

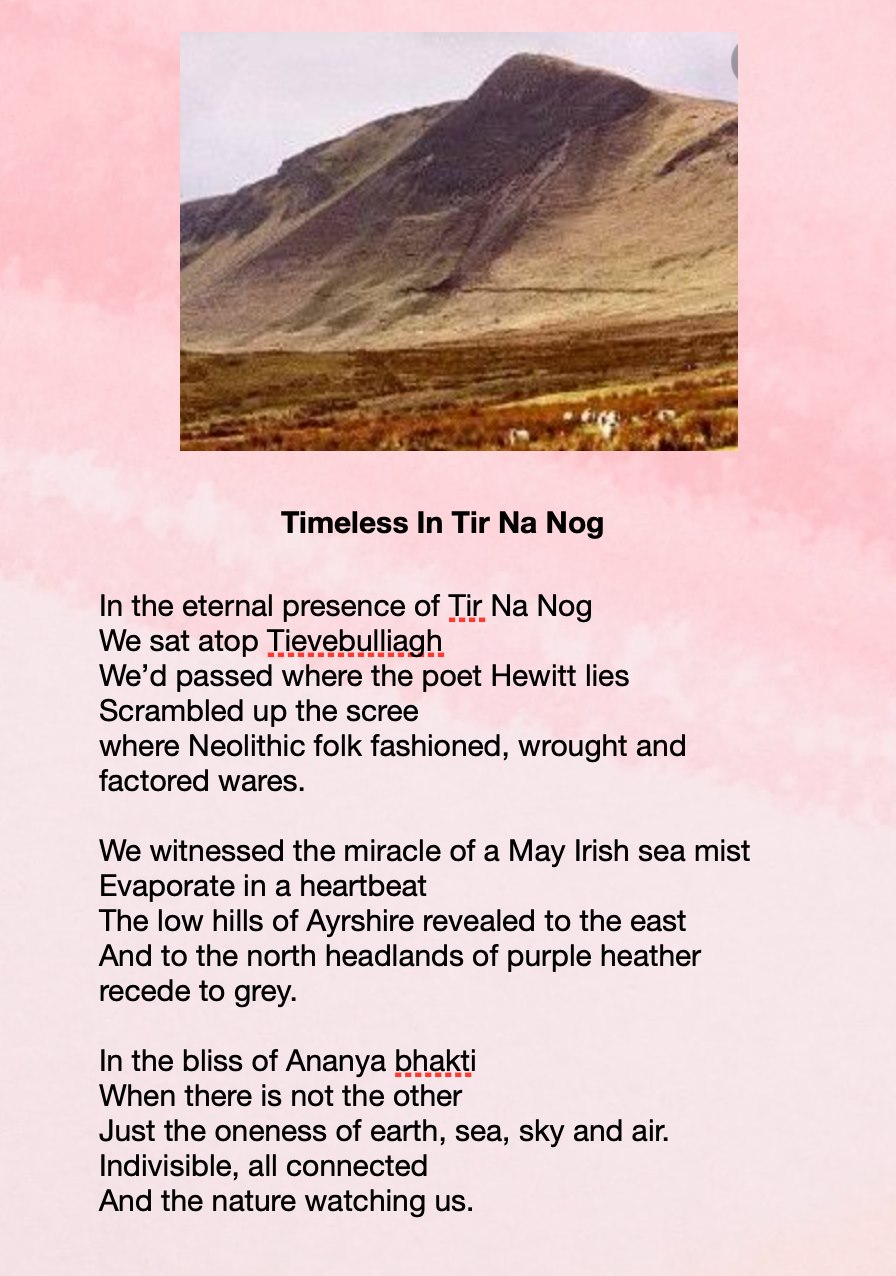

We sat atop Tievebulliagh

We'd passed where the poet Hewitt lies

Scrambled up the scree

where Neolithic folk fashioned, wrought and

factored wares.

We witnessed the miracle of a May Irish sea mist

Evaporate in a heartbeat

The low hills of Ayrshire revealed to the east

And to the north headlands of purple heather

recede to grey.

In the bliss of Ananya bhakti

When there is not the other

Just the oneness of earth, sea, sky and air.

Indivisible, all connected

And the nature watching us.

In May 1989, I was living in London, stressed, depressed and in need of a break. At the time, I was a founding director of Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, and to the outside world, I must have appeared to be a model of success – happily married with three lovely sons, etc.

I had always wanted to visit Iona, the island off the coast of Scotland where Irish Christian monks lived in the 6th Century, notably St. Columbus, one of those who first brought Christianity to Britain.

When I arrived at Heathrow airport, on a whim, instead of taking the shuttle to Glasgow, and on from there to Iona, without any solid reason for doing so, I decided to fly to Belfast instead and to make my way up the Antrim Coast Road and maybe take a boat over to Rathlin Island. Rathlin is where Robert the Bruce allegedly hid after his army was defeated by the English and a story is told of how he took refuge in a cave and watched a spider try many times build a web. It kept failing but in the end it was successful. Inspired by this, he again raised an army and this time was victorious over the English. The story apparently has no foundation in truth but that of course takes nothing from its power.

Back then, in 1988 or 1989, because of the Troubles, there was a security zone around Belfast airport and I had to take a taxi from the airport to near the town of Larne and from there I hitchhiked and walked my way up the beautiful Antrim Coast road.

One night I stopped at the town of Cushendall and checked into the local Youth Hostel. The place was empty apart from an Englishman and his wife who ran the place, and a lone German postman who was cycling up the coast. That night, in a pub in the town where I went to hear traditional music, a chance conversation with a local man resulted in him telling me that there was ‘a holy mountain' nearby. He explained that it was holy in pre-Christian Ireland and went on to say that it was called Tievebulliagh. On it there was a ‘Neolithic axe factory', an outcrop of blue granite and if one looked in the scree, (the countless small stones that littered the mountain face), one can find broken shards of axeheads discarded back in the Stone Age.

He told me too that there was a grave nearby that of Oisin, a 6th Century warrior/poet/king who famously, by the way the Christians subsequently told it, refused before St. Patrick, to convert to Christianity because, he said, he had been to the land of Tir na Nog, the land of the ever young. My take on this, is that he was already in a higher state of spiritual awareness and was playing with Patrick. The land of the ever young is the present, the here and now, and only realized souls can be there for long. Hence Christianity would have had little appeal or attraction for him.

I found the grave the next morning, some way out of the town and in farmland, and there was a heavy sea mist, with visibility down to about twenty meters or so. However, beside the grave was a plaque that said that local legend said it was the grave of Oisin, carbon dating proved that the grave was some 4500 years old. Oisin had lived in the 6th Century AD!

I walked past the grave through heavy mire and mud and began my ascent of the mountain. The atmosphere was eerie with a watery mist hanging suspended in the air. I passed cattle on the lower slopes where the ground was boggy and covered in patches of watery mud. As I commenced the climb, it was relatively easy going but I wasn't very fit and was soon out of breath. I found the scree and much as I tried, I picked up no stone that looked like it had been fashioned by human hand.

At this point the going became difficult for as I climbed up the scree, I would slide back to almost where I'd started from. This problem was solved by walking up at an angle, criss-crossing my way up in the manner I'd seen skiers move up a snow slope.

As I reached the summit, something strange and wonderful happened. I was quite out of breath, bent double with the effort and as I lifted my head, in that instant, the mist evaporated (which I'd read that sea mists often do). The fact that I knew it could and did happen did nothing to take away the magic of what ensued. Suddenly the sky was clear, cloudless and filled with sunshine. Looking across the sea I could see the low gray hills of south-west Scotland in the far distance and up the coast, headlands receding, one after another, progressively turning from purple to gray.

I was immediately transported to the present and was in a state of pure bliss where I was totally at one with all around, earth, sea and sky. I'd read of this state, but never before remotely experienced it and here it was, joyful and uplifting, life changing even. A big black bird kept swooping in low over my head which I thought meant that most likely it had a nest with some young nearby and it was trying to scare me off.

I had never forgotten as a teenager reading Wordsworth describing this state:

"And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things."

I had no sense of time and no desire to leave the mountaintop.

This area is known as the Glens of Antrim and eventually, as I started my descent, I came down another way, a glen which followed a small stream. It was the month of May and I passed trees bursting with new leaves, and hedgerows full of wild flowers of great profusion and vigor. It occurred to me that since those Neolithic times, not too many humans had gone where I had, maybe a few thousand at most. This was never a populated area and even for those who were here, unless they knew of the special nature of Tievebulliagh there was no great reason for climbing it.

That night I wrote an account of what had happened to me on my return to the Youth Hostel.

It had been a truly remarkable experience, a connection beyond my wildest dreams and the first time I had ever experienced anything that could be even vaguely regarded as spiritual.

Some eight years later, I took my new Russian Sahaja wife and son to the place. To my astonishment, what I had written down that very same day and experienced could not possibly have happened as I described it. In the pleasant spring sunshine, there was no mountain remotely near the grave and a map hastily consulted, revealed that Tievebulliagh was some distance away, a distance I most certainly never walked."